The design gap

We often discuss the term “Design gap” when giving lectures on design thinking. In this post, I explain where the term comes from and how you can use it in your design process.

Karl Ulrich (2012) defines design as: “conceiving and giving form to artifacts that solve problems.” What’s notable in this definition is that design must solve a problem. The problem doesn’t have to be very significant; it could be about enhancing an experience. Design comes into play when there is a gap in the user experience: “design is part of a human problem-solving activity beginning with a perception of a gap in a user experience, leading to a plan for a new artifact, and resulting in the production of that artifact.” A design gap exists when the desired situation for a user doesn’t align with the current situation.

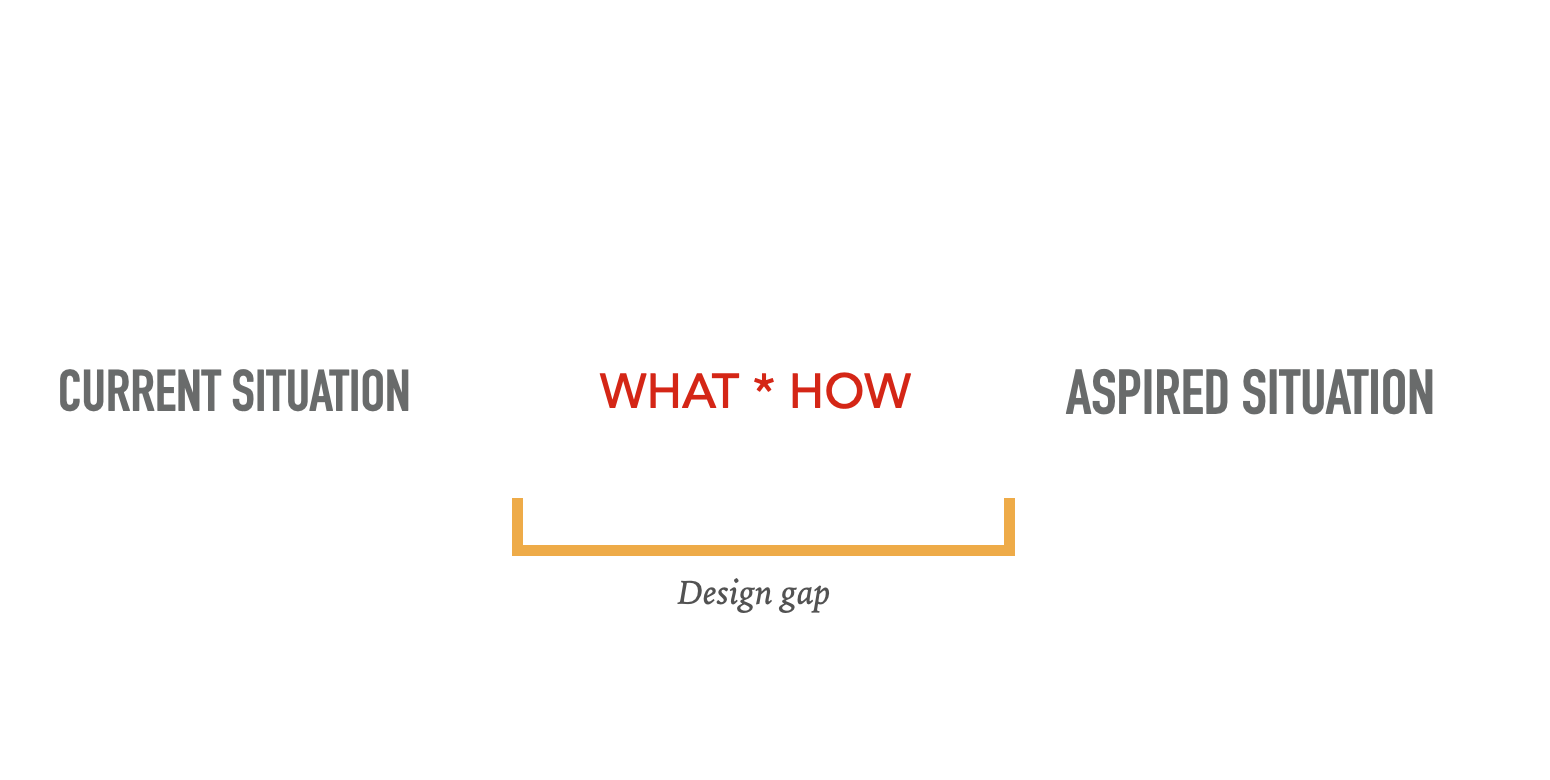

Design Gap

When defining the design gap for your project, you are expressing the tension between the current situation and the desired situation. Mentioning possible artifacts or solutions is not part of the design gap. It is clear, though, that an artifact (X) and a method (Y) need to be designed. In the schema, these are referred to as X * Y. If the final artifact is a pill, then the method discusses how often and in what frequency the pill should be taken.

At the start of a project, the current situation and the desired situation may not be clear. What problem needs to be described exactly? Which situations are actually achievable? This problem is called the designer’s paradox: “We cannot think about solutions until we understand the problem & We cannot understand a problem until we think about solutions.”

Throughout the project, the design gap can become more specific. Ultimately, the design gap will align with the intended situation.

Example Case

A client wants to explore the possibilities of VR Reality in the context of healthcare. There are ideas to work with exposure therapy for individuals with phobias. Exposure therapy often involves gradually exposing clients to what they fear.

At the start of the project, the design gap might look like this:

Current Situation

Clients with anxiety disorders have no simple way to be exposed to their fears in small steps.

Desired Situation

Clients can practice challenging situations on their own initiative. Clients can easily withdraw from these challenging situations if necessary.

Human-Centered Approach

Choose a human-centered approach when defining the design gap. It can be helpful to write from the first person’s perspective to clarify the user’s interests. Your clients may have different preferences for the project’s approach, and it’s essential to balance these with the user’s needs. Your client may be looking for a way to sell more, or expose the user to a certain kind of thinking. But what user problem/ need is solved by the purchase.

Multiple Design Gaps

In a project, there are often multiple design gaps, typically one for each target audience. In the example case, there could also be a design gap defined for a therapist. This might be about the therapist’s need to understand how the client is progressing with their treatment. Is the client practicing enough? Where are they encountering difficulties?

Methods

Select suitable methods to study both the current and desired situations. When examining the current situation, it often involves observing and developing empathy for the users.

To gather information about the desired situation, primarily use methods that obtain information from the client. Consider methods like Why-How laddering and context laddering.

Note

In management literature, the term “gap analysis” is also used. This term is unrelated to the design gap, and the methods used for gap analysis are not applicable to defining a design gap in human-centered design.